Play-action is, flat out, the best play in football on a per-attempt basis. On average, throwing the ball is also going to lead to more yards than running the ball. An average yards per attempt when throwing is at about 6.8 yards. Even rookie quarterback Davis Mills, playing for a talent-deficient Houston Texans team has a yards per attempt of 6.1. In case you were wondering, one of the best running backs this year in Nick Chubb is only averaging 5.8 yards per carry. So, even with Davis Mills at quarterback, it is still statistically beneficial to pass more than it is to hand it off to Nick Chubb.

Higher YPA when compared to normal dropback passing

Data also shows that quarterbacks average 1.39 yards more per attempt on play-action than they do on regular dropback passes. That’s not to say running the ball isn’t important – it is in the physical sense of the game and I’ll touch on that later. But, play-action gives more bang for your buck than any other play in football.

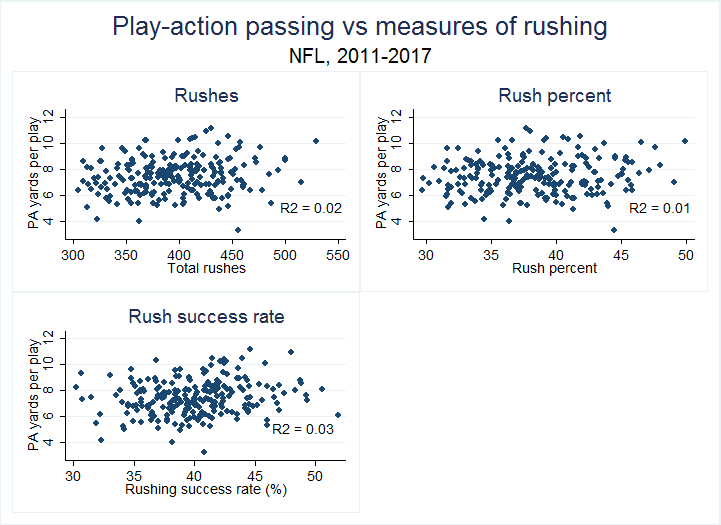

Play-action is not correlated to run frequency or effectiveness

Further, play-action effectiveness isn’t reliant on whether a team is good at running the ball or even if a team runs the ball at all. A limiting belief from coaches is that they have to establish to the run to be able to have effective play-action. Data does not support that. For years, play-action success rate has been uncorrelated to rush attempts and rushing success rate. Running play-action is just as effective when you’ve run the ball 30% of the time as it is when you run it 50% of the time.

What’s more, it doesn’t matter if you’re breaking off big chunks on those runs, either. That’s true in season-long data sets and within individual games as well. Regardless of how often a team has rushed in subsequent plays or how well they rushed in subsequent plays, the yards per attempt on play-action remain stable and higher than normal dropback passing.

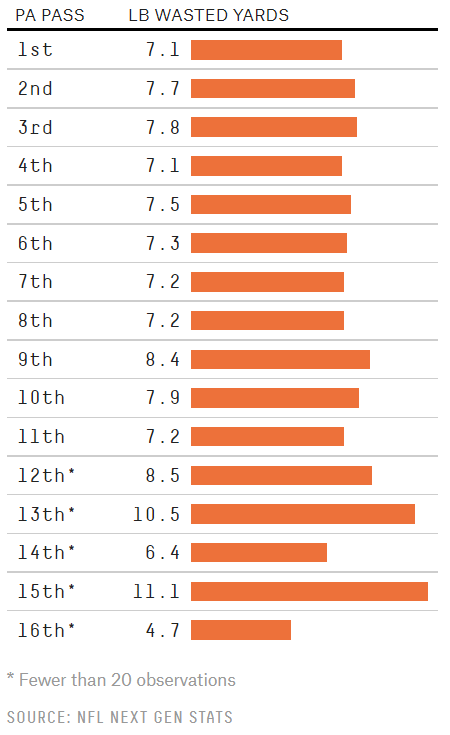

Play-action passing doesn’t have diminishing returns

Play-action also doesn’t have diminishing returns. Some coaches and fans may think that the more that you run play-action, the less reactive the defense will be. That has also turned out to be untrue. In tracking linebacker movement with NextGen Stats, Josh Hermsmeyer with FiveThirtyEight found that linebackers are just as reactive on the fist play-action pass of the game as they are on the 11th play-action pass of the game.

Under center vs. shotgun play-action passing

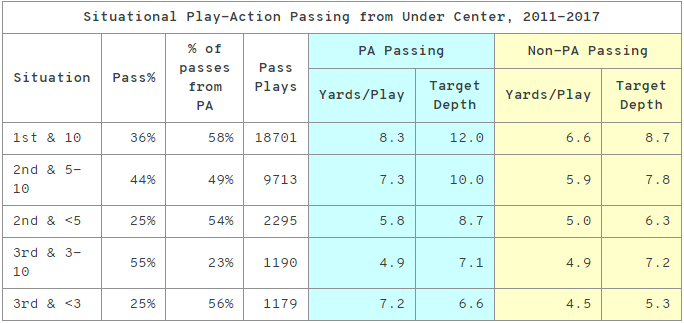

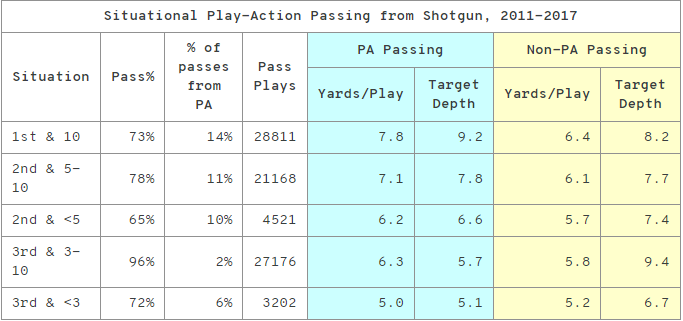

However, play-action isn’t a catch all in all situations. The threat of the run has to be present. Running play-action on 3rd and 10 isn’t as impactful as running it on 3rd and short. While the long down and distance situation doesn’t lend itself to running play-action, almost every other situation does. On first down, 2nd and any distance, and 3rd and less than three, play-action had a higher yards per play average than normal dropback passing did. That is true for play-action while under center and while in shotgun. However, depth of target and the yards per play disparity is lower while in shotgun. Never-the-less, however you’re running play-action, it’s still more effective than non-play-action passing.

Having a deeper depth of target is not insignificant, either. Maybe unsurprisingly, data shows that yards per play increases with depth of target and intended air yards. Overall, despite the potential risk for more incompletions, throwing at deeper targets results in a higher average yardage gain than throwing at shallower targets.

While teams do favor play-action on their under center pass plays, they still run 64% of the time overall when under center. The data just doesn’t support running the ball at that rate. Even more, the play-action rate from shotgun vs. under center is surprisingly low while in similar game situations. That’s despite shotgun play-action still being more effective than normal dropback passing. For example, on 1st and 10, teams ran play-action 14% of the time while in shotgun versus 58% of the time while under center.

Kyle Shanahan’s Play-Action Scheme

Don’t abandon the run

That isn’t to say that the run game doesn’t have a place – it does. And it’s perhaps most well-said by Brandon Staley: “But what the running game does for you, it brings a physical dimension to the football game. And what the running game does that the passing game does not, is the running forces the defense to play blocks and to tackle. That happens on a run play — You must play blocks and you must tackle. In the passing game, those things don’t need to happen, right? You don’t have to play as many blocks. And you may not have to tackle based on incomplete or not. So what the running game does is it really challenges your physicality and that’s why I think the run game is important to a quarterback. It’s literally going to allow him to have more space to operate when you do throw the football.”

The run game brings a different element to an offense. I’m not saying don’t run the ball – especially situationally and as a function of ball possession and creating balance within your offense. The old adage that there are three things that can happen when you throw the football and two of them are bad is true. On a per-play basis, though, play-action should rise in its use across all styles of offense. That is especially true when compared to regular dropback passing.

Mechanics of the play-action pass

Part of the reason that play-action can be so impactful, is that the depth of target is tied to the mechanics of how play-action works. With linebackers coming up to defend the run, that puts them into the throwing lane of shorter passes. As a result, the intermediate and deep routes are thrown more frequently. In fact, the completion percentage for passes under seven yards off of play-action is actually lower than that of passes over seven yards on play-action.

Play-action pass concepts

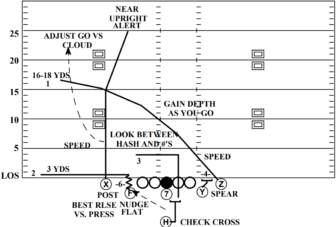

That’s why concepts like Sail and Yankee can create big gains in the play-action game. Especially out of shotgun, you can attach almost any passing concept to run fakes, but Sail and Yankee are under center boot and play-action plays.

Sail overloads one side of the defense with three routes at three different depths. As long as the offense works within that framework, there’s almost an infinite number of ways to run Sail. With that spacing, the defensive zones are flooded with three receivers against two defenders. That puts those defenders in conflict. The vertical route is usually used to clear out the deep defender. The offense is then able to put the flat defender in a high-low read on the intermediate and flat route. Based on how we know defenses react to the play-action, that means the intermediate route is often open.

Sail Concept

Yankee, on the other hand, is a two-man route concept that is primarily used out of run-heavy formations to attack single-high safety looks like Cover 1 or Cover 3. It’s a deep shot play that puts the middle field defender in conflict with a deep over route and a post behind it. The deep over is designed to tempt the deep safety to come up in combination with the play-action. That opens up the middle of the field. If a team is playing Cover 3 or Cover 1, that deep post has leverage on the corner and access to the middle of the field behind the safety. If the play-action is effective, that also removes linebackers from getting into the lane of the deep dig.

Yankee Concept

Final thoughts

There needs to be more play-action passing in almost every situation on the football field. There aren’t diminishing returns on its use, you don’t need to run the ball to use it, and it adds explosive play potential to every pass play. Even the highest percentage teams only use play-action on about 30% of pass plays, but the data all says that it’s the best play in football.